Scripts for the ear

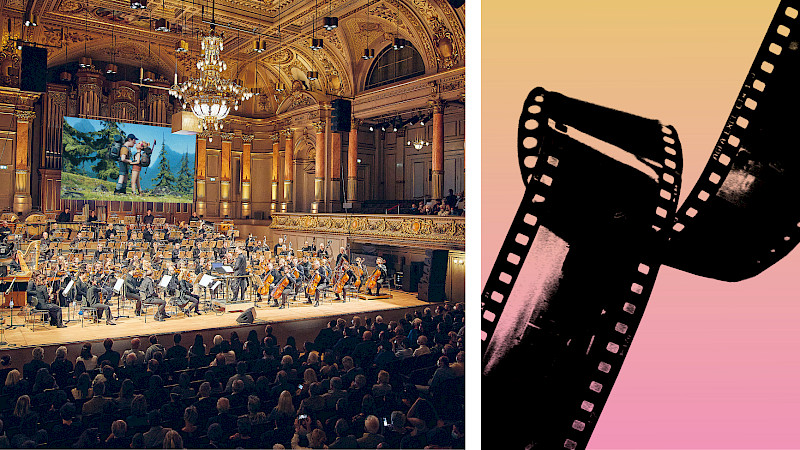

His film scores for Italian westerns are among the most famous soundtracks of all. But Ennio Morricone also composed something completely different.

Anyone who hears the name Ennio Morricone immediately has a whistled melody in their head, or the lament of a harmonica, or the buzzing of a jew's harp. In any case, something that sounds like desert and vastness. The Roman composer, together with his former primary school colleague Sergio Leone, not only invented the genre of the spaghetti western - he also created sonic ciphers for it that are as unmistakable as they are unforgettable.

They earned him a lifetime achievement Oscar in 2007 and a fame that he found rather than sought. Originally, he had his sights set on a completely different career, one as a passionate avant-gardist. In conversation with him, we learnt how much he ultimately remained one: he was not a film composer, but a composer, as he liked to emphasise. And he pointed out that, in addition to around 500 soundtracks, he had also written quite a few other things, namely chamber music and piano pieces, orchestral works, cantatas and an opera.

He started out as a trumpet player, like his father. But while his father made light music, Ennio Morricone travelled with an experimental ensemble after completing his concert diploma - and also studied composition with Goffredo Petrassi. in 1958, he travelled to the Darmstadt Summer Courses as part of a radical generation that also included Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen, Luigi Nono and Luciano Berio.

But since, as he said, "you couldn't feed a family with new music", the father of four had to come up with more lucrative projects. So he composed and arranged canzoni for Milva, Mina and Gianni Morandi. And after a few unsuccessful attempts in the film industry, he made his breakthrough with the soundtrack for Sergio Leone's "Per un pugno di dollari", which earned him considerably more than a handful of dollars and settled the financial issue for the time being.

Los Angeles? Better not

From then on, he was in demand far and wide. Not only Italian directors such as Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci and Ettore Scola wanted music from him, but Hollywood also took notice of the shy Italian, who turned out to be remarkably stubborn. A villa in Los Angeles? He turned it down with thanks. He wanted to stay in Rome, and he didn't like travelling either. Anyone who wanted something from him had to come to him.

Many came, and they received very different things. Ennio Morricone not only knew all the emotional tricks, but also the history of music. He brought baroque patterns to a boil, pitted Sicilian folk music melodies against each other, and added double and triple bottoms to the harmonies. Even in his most palatable soundtracks, he smuggled an astonishing amount of atonality, and his vocabulary also betrayed the former avant-gardist: when his scores rattled and crunched, he spoke not of noises, but of "non-musical sounds".

He was undoubtedly pleased that one of his many fans was the composer Helmut Lachenmann, who deals with "non-musical sounds" in a completely different way. Morricone's music has an "irresistible aura", Lachenmann once said in an interview, "rationally I can't get to the bottom of it". Another fan was Quentin Tarantino - the last great director to travel to Rome. He had quoted Morricone motifs in a number of films (with and without permission), and now he wanted his own soundtrack for "The Hateful Eight". And the then 87-year-old composer once again sat down at his desk as usual from 7 a.m. to 12 noon and wrote the music that would win him his second Oscar in 2016.

First the music, then the film

However, when asked about his collaboration with Tarantino, Ennio Morricone complained quite openly that Tarantino ended up being "too free" with the score. This fundamentally contradicted Morricone's aesthetic: he saw a soundtrack as a work, not a collection of material. He also composed in such a disciplined way because he wanted to have his score ready before the start of filming, "because that way you can shoot the scene a little longer or shorter". As reserved as he appeared, he was firmly convinced that the music in a film was just as important as the images.

Sergio Leone probably understood this best of all. During the filming of "Spiel mir das Lied vom Tod", he had the already completed soundtrack played as a "script for the ear" - in the knowledge that this would influence the protagonists. Leone had given his sounds "enough space", said Morricone, namely just as much as is needed for music that has far more to offer than a little atmosphere.

When Ennio Morricone died on 6 July 2020, the magazine "Der Spiegel" summed it all up beautifully in the last sentence of the obituary: "A more important composer has never given cinema a gift."

We use deepL.com for our translations into English.