Zen or the art of labelling

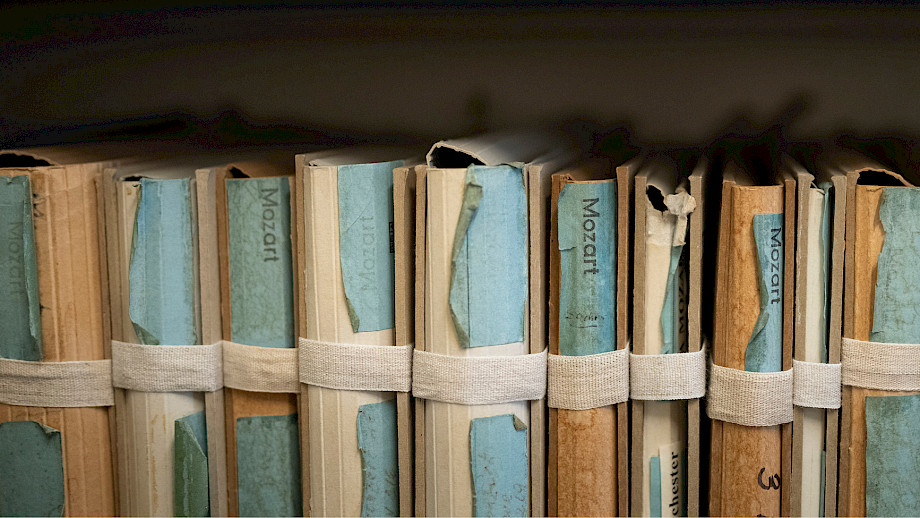

When the sheet music arrives, a lot of the library work has already been done. Now the finishing touches begin.

The tasks of an orchestra librarian are many and varied. She plans and organises, researches, documents, does manual work, and marking is regularly on the agenda. To be more precise: the manual insertion of bowings, dynamic and articulation marks in the sheet music with a pencil.

The concertmaster and subsequently the section leaders of the second violin, viola, cello and double bass determine a bowing system for their group that harmonises with the rest of the string registers. The library staff transfer these from the first desks to the tutti. The conductor's wishes regarding dynamics and articulation are added if necessary, they are taken from the conductor's score. This is a labour of patience that can take many hours, depending on the size of the work, the complexity of the arrangement and the condition of the orchestral parts. For a newly labelled Mahler symphony with up to 50 pages per booklet, it may take a whole week.

Clearly legible, even handwriting is essential. The marks are made with a soft pencil that can be easily erased when corrections are made in the orchestra rehearsal. The aim is to make the musicians' note-reading flow as pleasant and effortless as possible in the concert situation by providing information that is as simple as it is precise. The symbols for the downstroke and upstroke are placed in the centre above the note head, and if there is no space there, further up or in a clearly visible position a short distance away. For musical abbreviations, a slightly curved line guides the eye from the end of the last bar played across the page to the beginning of the new bar - a signpost that makes the leap appear harmonious and logical.

No chance for AI

When outsiders hear about such an activity, they sometimes wonder why it is still performed by a human and not an AI-controlled robot. In fact, it would probably lead to relatively poor results if the characters were copied into the voices by machine. Human-intelligent responses to individual situations are too important here. Personal knowledge of the orchestra is also an advantage - every orchestra, every string section has preferences and habits that need to be taken into account. And if the template specifies a division for "divisi" passages (where individual desks or musicians have to play different parts), this must be adapted individually in each booklet.

Whether additional information such as dynamics and articulation are adopted is often decided on the basis of considerations regarding their validity in the work, the conductor's wishes and those of the musicians. These can sometimes be contradictory (should every piano be additionally emphasised? Certainly not! But perhaps one or the other should...).

If you take all these requirements into account, it becomes clear that the work of patience must be accompanied by an ever-watchful concentration that keeps an eye on the current sign, its aesthetic execution and the context. Over time, however, the hand acquires a certain sureness, a practised attentiveness of the mind that allows the mind to detach itself somewhat and virtually float above the activity. This gives it an almost meditative quality at times. And the prudent mental exercise is accompanied by the satisfaction of providing the orchestra with optimal working material within the given framework.

We use deepL.com for our translations into English.